1. What do we mean by Lived Experience?

Good lived experience engagement is about genuine collaboration and including People with Lived Experience in decision-making processes that effect them. Done in a non-judgemental and safe way that includes a diversity of experience, it values the wisdom and experience of people who have lived with the consequences of being excluded from decisions about their lives.

2. Guide to working with People with Lived Experience

This guide highlights the importance of community service organisations engaging People with Lived Experience, as their insights reveal gaps that service providers may overlook, resulting in outcomes better aligned with the needs of their communities. People with Lived Experience have a right to agency and to actively participate in shaping decisions that affect them, particularly when current service approaches often fall short. Their involvement ensures resources are redistributed more equitably and helps service providers and funders better understand the real impact of their work.

3. Do No Harm: Equitable practice

This guide emphasises the need to approach collaboration with an understanding of power dynamics, equitable practice, and the importance of avoiding harm. Effective engagement requires recognising how power imbalances affect relationships and addressing practices that may unintentionally exclude or harm participants. As Brooke Prentis, a Wakka Wakka woman, reminds us, traditional approaches such as expecting everyone to meet at the same time can reflect colonial systems and are not always feasible or inclusive.

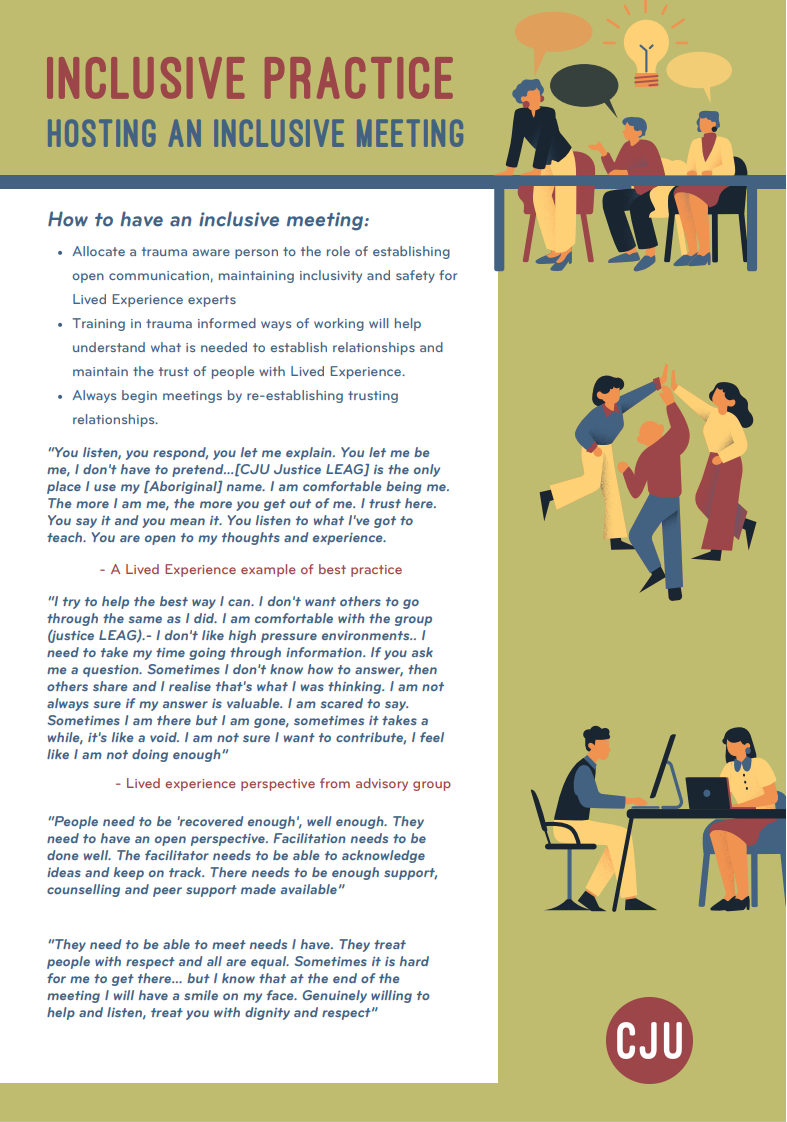

4. Meeting inclusivity considerations and needs

This guide highlights the importance of inclusive practices when hosting meetings involving People with Lived Experience. As shared by a member of the Climate Justice Unions’ Lived Experience Advisory Group, effective facilitation requires respect, openness, and a focus on dignity. Meetings should provide adequate support, such as counselling, peer support and debriefing, to ensure participants feel safe and valued. To foster inclusivity, organisations should allocate a trauma-aware person to maintain open communication and ensure safety. Training in trauma-informed practices helps establish and sustain trust. Always begin meetings by re-establishing relationships to create a supportive and inclusive environment for meaningful engagement.

5. Developing the Climate Justice Union’s Justice Lived Experience Advisory Group (LEAG)

This guide explains how the Climate Justice Union (CJU) created the Justice Lived Experience Advisory Group (LEAG) to ensure that the voices of those most impacted and least heard could meaningfully shape their climate justice work. To achieve this, CJU focused on building relationships, understanding needs, and fostering equity. Membership was sought through existing connections, enabling sufficient support and accommodations, such as addressing peer needs, providing professional supervision, and offering technology access and recovery time.

6. Why young people want to be involved in climate justice

This guide highlights why young people are motivated to engage in climate justice and the importance of supporting their involvement. Activism provides young people with a sense of agency and hope, enabling them to channel their energy and frustrations about climate change into collective action while building connections with like-minded peers. However, the burden of climate work can lead to burnout, making it essential to create spaces where young people feel supported by family, friends, and mentors. Empowering young people to participate in action for climate justice builds their resilience, collective efficacy, and agency, strengthening their ability to contribute to mitigation and adaptation strategies. Supporting their wellbeing is critical to ensuring sustained and meaningful engagement in climate justice efforts.

7. Managing money

This guide highlights the importance of recognising and valuing the contributions of People with Lived Experience, including Aboriginal Elders and people with disabilities, in climate justice and disaster resilience work. It explains why equitable remuneration is critical, what organisations and participants should consider and provides a simple process for paying people fairly. Developed by People with Lived Experience at Climate Justice Union, this resource shares lessons learned to support community service organisations.

8. Media and narratives

This guide provides community service organisations with a framework for ethically and responsibly working with People with Lived Experience of climate impacts and structural disadvantages in media contexts. It offers practical steps to ensure that their stories are treated with respect, dignity, and alignment with their experiences and values.

9. Media and stories – a guide for People with Lived Experience

This document provides guidance for People with Lived Experience who may wish to share their stories with the media. It highlights important considerations to ensure that storytelling remains a positive and empowering experience while mitigating potential long-term impacts.

Key recommendations include reflecting on who benefits from sharing your story and the purpose it serves and ensuring opportunities to review and edit before publication. Participants are encouraged to ask about withdrawal policies, pseudonym options, and remuneration for their time and labour.

10. Creating a child-safe environment is climate justice

This guide highlights the importance of creating a child-safe environment within climate justice and disaster resilience efforts, emphasising the need for organisations to be mindful of young people’s well-being while supporting their activism. Many young people are already engaged in multiple causes and may face burnout or anxiety, so it’s crucial that organisers recognise their duty of care.

The boundaries of responsibility and accountability can be complex, as organisations may either avoid involvement to limit liability or overcompensate by treating young people like adults and neglecting necessary protections. This guide outlines three practices for engaging young people that address these complexities, ensuring a safe, supportive environment for participation in climate justice efforts.

Organisers have both a moral and legal obligation to protect young people from harm, discrimination, and exploitation. This includes managing power dynamics to prevent potential risks, such as predatory behaviour, and fostering an environment that prioritises safety, respect, and autonomy for all participants.

11. Disability, chronic illness and climate

This graphic explores the cascading impacts of climate change on people with disabilities, chronic illnesses, and those experiencing poverty. These impacts include increased stress, pain, injury, displacement, lack of vital healthcare, respiratory illness, and isolation. For many, these challenges are compounded by barriers to accessing support and resources, leaving them disproportionately vulnerable to climate-related risks.

This document is part of a broader body of work, developed through discussions and conversations held online and in person during 2023 and 2024. It represents a collective effort by community members and Climate Justice Union contributors with lived experience of disability, poverty, and chronic illness. While it offers insights and shared stories, it remains an ongoing and evolving project aimed at amplifying the voices of those directly impacted by these challenges.

12. Homelessness, poverty and climate change

This document comes from community yarns conducted in Western Australia in 2023 and 2024, co-designed with colleagues who have lived experiences of homelessness and support individuals currently experiencing homelessness. It reflects the insights and contributions of people in recovery, those with existing support systems, and individuals experienced in sharing their stories to shape policy and practice. Participants included people living in poverty, many of whom had been involved in climate justice activities.

The small group represented diverse and intersecting identities and structural disadvantages, including young people who experienced homelessness and poverty, individuals with significant health and mental health concerns, and those affected by substance use. The group also included regional residents and members of communities facing systemic racism, neurodiversity, domestic violence, and the housing affordability crisis.

Their input identified barriers to climate adaptation for people experiencing homelessness and poverty while offering solutions rooted in lived experience. One participant reflected,

“This is the first time I’ve ever thought of (my lived experience) as being worth something.

Because there’s always been like my experience in life as a black fella, there’s always people speaking for us and doing for us.

So we haven’t really had a say.”

Read more

Connection and Community – Transformative Lived Expertise-led Approaches 2024 – 2029 (Mind, help, hope and purpose)

Lived Experience (Shelter WA)

Mind’s Lived Experience Governance Framework (Mind, help, hope and purpose)

Lived Experience Framework – Principles and practices for Lived Experience partnership (WACOSS )

Lived Experience (Peer) Workforces Framework (Mental Health Commission, Government of Western Australia)

Lived Experience Framework (South Australia’s Housing and Homelessness System)